The man I remember as my great grandfather was a fit, bespectacled man with thinning white hair and a kind smile. Wearing a starched white shirt, black pants, and a dark tie, he sat on the grass in a lawn chair one hot, muggy, Wisconsin afternoon, proudly watching his children and grandchildren enjoy spending time together. Even over-dressed for a party at the lake, I don’t remember seeing him sweat. He was blissfully happy, surrounded by everyone he loved. I can hear his sweet laugh and see his kind smile as I burbled sweet nothings and probably soiled my diaper as only a one-year-old can do.

It my was first family reunion, and I only remember it because of the photos. That’s one of the perks of having a father who was a photographer: He documents everything using his camera. We were at the family lake house, where my mother’s athletic and outdoorsy cousins tried to teach my father how to waterski. Someone not-so-talented-with-a-camera caught those waterskiing lessons in blurry snapshots. My mom was helping her mother prepare food in the cottage kitchen. We have a photo of that, too, with both women in no-nonsense aprons, toiling over a small stove, probably boiling bratwurst that would be grilled later in the day. My great grandfather’s job was to keep me entertained, and he gave it a valiant shot, rocking me on his knee.

I would give anything to go back to that day as an adult so I could talk to my great grandfather, Carl Fritzler, about his life in Grimm, Russia, his immigration to the United States, and how he came to settle in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. He and my grandparents were the only links to my family’s past; everyone else was gone. That family reunion was more than 50 years ago, but I think about it often, now that I am so involved in researching my family’s history.

Thanks to my DNA test results, I was able to connect with the family of a woman who was Carl’s niece, the daughter of his sister Mollie Fritzler Schneider: Frieda Schneider Grotegut. My mother knew nothing about the Schneider family, probably because Mollie Schneider died unexpectedly in 1926, and the families drifted apart. My mother wouldn’t be born until the 1930s, so she had never known her great aunt Mollie and she probably never met her great uncle Philipp.

I read to my mother from the note that Frieda’s family sent to me:

“Carl Sr. was a very religious man and always sang and hummed hymns. He was a very good looking man and you could sit down and have a good conversation with him,” his niece recalled. My mother’s face went pale before lighting up with joy. “That was my grandpa,” she whispered. It was the only confirmation she needed.

After several notes back and forth with Frieda’s family, culling through my own family information, and searching for what I didn’t know on the Internet, I was able to come up with a biography for my mother’s beloved grandfather. This biography is my gift to my mother.

CARL FRITZLER was a fourth generation Volga German, born in Grimm, Russia, on February 28, 1880 to Johann Jakob Fritzler and Katharina Elisabeth Schäfer. The Fritzlers were descendants of Hanß Jakob Bauer Fritzler, born in 1688 in Kleingartach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, Germany. His son Hanß Jakob Fritzler and his wife Franziska Catherina Eurich and their children were among the original settlers of Grimm in 1767. Both families were considered Evangelical, as opposed to Catholic, although the Colony of Grimm was considered a Reformed Protestant settlement.

Carl’s wife was Eva Kraft Schott, born September 18, 1886, also in Grimm, to Johann Friedrich Schott and Eva Katharina Kraft. She was descended from Jakob Schott and Anna Margaretha Becker, and Adam and Susannah Kraft, four of the first settlers of Grimm. The Krafts were also Evangelical Lutherans from Mittelbrunn, Pflaz, Bayern, Germany, while the origin of the Schotts was Holzgerlingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg.

Germans from Russia lived a difficult life which did not resemble the original descriptions and promises of Catherine the Great. By the late 1800s, Volga German families began to immigrate to the United States and Canada, looking for a better life. Scouts came over first, checking out different areas in the United States, looking for the best places for their friends and family to live. Once they were settled, they returned to Grimm to escort families to America.

Encouraged by the safe travels and good fortune of these scouts, Carl began to plan a move for his own family. His plans were delayed when he was drafted into the Tsar’s Army, which, in turn, only made his urge to leave Russia stronger. Volga Germans were pacifists and had been promised no conscription by Catherine the Great. A century later, the ruling Russians backed out of that promise and regularly called on them to serve in their Army. Somehow Carl managed to get a plum job as a guard for the Tsar, avoiding the dangerous battle fronts. At the conclusion of his service, he began to finalize his plans to leave Russia.

Although the big cities were nice, Volga Germans were interested in moving to an area where they could immediately be successful, which meant a place where they could farm. They discovered that the Midwest and Plains States held the most promise because the terrain resembled that of the Russian Steppes, where Grimm was situated. Families began to immigrate to the United States in the late 1800s and the early 1900s.

Carl and his family, along with his sister Mollie Fritzler Schneider and her family, left Russia at the end of 1912. First they traveled by train from Saratov to Libau, Latvia, a trip that took about two weeks. From there, a small ship took them on the first part of their ocean voyage from the European mainland to England. About two weeks later, they traveled from Liverpool, England, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada on the S.S. Canada. The passenger manifest for their ship confirms the families travel along with other relatives and friends.

Carl Fritzler’s family, from top left: Mollie, Eva, Ann, Emily, Carl and Edward Fritzler, circa 1920.

Years later, Carl’s brother-in-law Philipp Schneider recalled their journey to America for his granddaughter Janelle Zimmermann, who documented the conversation via a taped recording. We were introduced to each other thanks to a DNA match, and she generously shared with me the information she had from her mother, Frieda Schneider Grotegut, and her grandfather Philipp Schneider. One note from her conversation with her grandfather read, “He came to America leaving Grimm, Russia on November 27, 1912 and reached America January 13, 1913. They left by railroad to Libau, Finland.”

The reference to Libau, Finland puzzled me. Libau is a Latvian city. I double checked to make sure there wasn’t another Libau in Finland; there was not. If they traveled to Libau, they traveled to Western Latvia directly west from the Volga villages. It was curious that Philipp mentioned Finland at all, since Finland is far northwest of the Volga region of Russia.

When families left Grimm for a port that lead to America, they usually traveled northwest by train from Saratov to Moscow, and then due west or southwest to the port city. It they were traveling to Libau, now called Liepaja, in Latvia, they would probably continue due west from Moscow to Riga and finally Libau. Some trains traveled north to Minsk first, and then down to Libau. The shortest, most direct route from Saratov to Libau is a little over 1,200 miles; it was much longer if they reached the Baltic via Minsk or Finland. Without any documentation today, it’s difficult to determine which way the Fritzlers and the Schneiders traveled from the Volga River to the Baltic Sea.

Records show they took a small ship from Libau, Latvia, to Kingston upon Hull in Yorkshire, England, the latter more commonly known simply as Hull. Further research showed there were two shipping lines that provided passenger service from Libau to Hull:

- The Wilson Line of Hull, England: It mainly transported passengers between Norway and England.

- F.Å.A.: This was an acronym for the Finnish Steamship Company which transported passengers from Helsinki and Libau to Hull.

Because Philipp Schneider clearly mentioned Finland in his story about his journey to America, it seems logical that he meant they boarded a Finnish ship, not that they actually traveled to Finland before heading south and west.

Wikipedia confirmed the Finnish Steamship Company Finska Ångfartygs Aktiebolag was also known as F.Å.A. Their ship was the S.S. Titania, primarily used to transport emigres from Finland to Hull, although it made stops along the way in Libau and Copenhagen, picking up and transporting Russians and Jewish Latvians in addition to Volga Germans. Based on Philipp’s recollections, this seems the likely company they used to transport their families to England.

For the record, Germans from Russia were technically Russians in terms of their citizenship and passport documentation. That said, however, the Volga Germans considered themselves a separate group of people for more than 150 years, never intermarrying with Russians or any other ethnic minority in Russia. Their names remained German and their primary language was German, although some had picked up Russian as a second language.

According to the Genealogical Society of Finland, while some ships traveled from Helsinki to Hull, some ships carried Russians directly from Libau to Hull. “Apart from Finns, the volumes record thousands of Russians, a number of Estonians, Latvians and Livonians” who traveled on Finnish ships. “Many of the Russians have Jewish names, but even German names are common…It is unclear whether all Russian emigrants traveled by way of Hanko [Finland], since F.Å.A. boats carried Russian emigrants from Libau to Hull without calling at a Finnish port.”

I searched for a copy of the F.Å.A. passenger lists from 1912. Copies of the passenger lists up to 1910 and after 1918 exist; the lists for passengers traveling between those years are either not available or were destroyed.

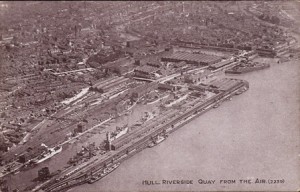

According to Philipp Schneider, the journey on the S.S. Titania from Libau to Hull took four days, which meant the two families arrived in England December 15-18, 1912. The ship docked at the Riverside Quay, a dock built specifically to handle quick turnaround ocean vessel traffic at the port. A rail station adjoined the quay, allowing European travelers to conveniently board a train that took them to Liverpool where they would board larger ocean liners that headed to America.

The Fritzlers and the Schneiders spent 17-19 days in England prior to boarding the S.S. Canada in January. Some of that time may have been spent traveling. It’s unclear whether the families were able to take a train directly to Liverpool from Hull or if they traveled south to London and then northwest to the port city.

According to historical records, once the passengers arrived in Liverpool, they were not allowed to board outbound ships until the day before or the day of departure. If they arrived earlier than that, they were forced to stay in lodging houses. Unfortunately, the lodging houses had a reputation for being crowded and unsanitary. By the turn of the 20th century, however, the steamship companies had stepped in and put emigrants up in company-owned lodges that were cleaner and less crowded. Although conditions in the early 1900s were better than those 30-50 years earlier, there were still complaints. It’s difficult to imagine which was worse: lodging accommodations in the Liverpool or steerage class on board a ship. Knowing this makes it clear how horrible the conditions in their homeland must have been. Uprooting families and enduring the long, uncomfortable journey to America was a small price to pay for the chance at a better life.

After the Fritzlers and Schneiders spent more than a couple of weeks in a lodging house, they boarded the S.S. Canada and departed for America on January 4, 1913. The voyage across the Atlantic normally took 10-11 days. Some ships traveling across the Atlantic made a stop in Ireland to pick up additional passengers. Since their ship made the voyage in only 9 days, they probably bypassed Ireland and headed straight to America, reaching Nova Scotia, Canada on January 13, 1913.

Carl’s brother-in-law remembered what the families paid for tickets on the steamers: $150 per adult, $75 per child, and $8 for infants under two years of age. Most likely they traveled 2nd class or steerage. Pre-warned by the scouts about the food service, they brought plenty of black bread and sausage from home to supplement their diets. Philipp recalled that the ship meals included bear meat and fish, among other things, and that, frankly, the food wasn’t very tasty. Even though they dipped in to their personal food supply, the families still managed to make their bread and sausage last more than a month, until shortly before they arrived in Chicago.

After the ship landed in Nova Scotia, Canada, passengers going to the United States were transported over the border where they were processed in Portland, Maine. From there the families took a train to Chicago where they stayed with two different families. Carl and his family stayed with the Albrandts, extended family members of the Fritzlers, while the Schneiders stayed with Herman Schuette, Philipp’s cousin.

Carl Fritzler chose to take his family to Colorado where there was already a large population of Volga German immigrants. He may have homesteaded land there, although I haven’t yet found any record of it. During those first years, the family worked for the sugar beet companies in the Greeley area. Working in the fields was back-breaking work, and not even the children were spared from pulling beets during the harvest season.

Carl eventually saved enough money to purchase a home in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. Fond du Lac was another city with a large population of Germans from Russia, including Carl’s sisters Mollie Schneider, Elisabeth Trott, and Eva Felde and their families. He and his family finally settled in a house at 180 Doty Street, just one block away from Rueping Leather Company, where Carl was employed. He was a faithful worker there until he retired in 1947.

He was very religious, not only as a member of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Fond du Lac, but also as a member of the German Brotherhood. The Brotherhood was based on the Mennonite Brethren Church in Russia; its members practiced a stricter version of their Protestant faith which required them to renounce military service and adhere to a simple way of life, among other things. When Grimm residents immigrated to the United States, they brought this form of worship with them. Here it was called the German Brotherhood, and it offered former Volga German residents a way to meet regularly, worship and honor the traditions that they had in Russia.

Carl was an honorable family man, quiet and kind, and very close to his five children and their families. They had regular, large get-togethers both in the Fond du Lac area and at a lake cottage owned by his grandson and his wife. Carl and Eva often traveled around Wisconsin, Illinois and Michigan, visiting other Grimm residents who had also immigrated to the United States. Many of those people were extended family members with whom they remained close for the rest of their lives. Carl was known far and wide for his frequent humming, usually of his favorite hymns, often while sitting in a rocking chair on his front porch.

Four years after losing his wife Eva to the after-effects of a stroke in 1959, Carl died in 1963. The couple is buried at Estabrooks Cemetery in Fond du Lac.

Quotes and Links

“The export of butter to the UK required regular sailings and vessels equipped with refrigerated cargo space, and the company placed it’s best ships on this service between Hanko and Hull, and later between Turku and Hull. They were also heavily involved in the transport of Finnish emigrants to Hull on their way to America and by 1932 had carried nearly half a million passengers on this route. (See Transmigration via British Ports).” So butter was shipped to the European continent on the outbound trip, and immigrants filled the ships on the return trip. http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/lines/finland.shtml

“Finland Steamship Company (Swedish: Finska Ångfartygs Aktiebolag, abbreviated FÅA, Finnish: Suomen Höyrylaiva Osakeyhtiö, abbreviated SHO) was a Finnish shipping company founded in 1883 by Captain Lars Krogius. In Finnish and Swedish, the company was usually referred to simply as FÅA. In 1976, the company changed its name to Effoa, a phonetic spelling of the abbreviation FÅA.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finland_Steamship_Company

“Unlike many other immigrants to the Americas during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Germans from Russia wanted to continue farming and settled in agricultural areas rather than industrial cities. Primary areas were the Plains states of Illinois, Nebraska, Kansas, North and South Dakota, with some movement to specific areas of Washington and California (Fresno and Lodi for instance) in the United States; Saskatchewan and Manitoba of Canada; and Brazil and Argentina. These areas tended to resemble the flat plains of the Russian steppes. In addition, the upper Great Plains still had arable land available for free settlement under the Homestead Act.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germans_from_Russia

“Finland Steamship Company’s Emigrant Ships: S/S TITANIA. Passenger steamer, one deck & spar deck, Passengers: Deck I: 86, Deck II: 68,Deck III: 585. Ice class: 1. Tonnages: 3,495 GRT, 1,997 NRT, 1,940 tdw. Length over all: 100.60 m. Breadth: 13.65 m. Draught: ?. Engine: Triple steam engine 3 cy. by the shipbuilders. Horse powers: 4,500 IHP. Speed: 14.5 knots. 31.8.1908. Completed by Gourlay Bros. & Co., Dundee, as S/S Titania for Finska Ångfartygs Aktiebolaget, Helsinki. Sailed on Helsinki/Hanko – Copenhagen – Hull line. 14.3.1916: Requisitioned by the British Admiralty. Converted to an armed accomodation vessel and renamed HMS Tithonus. 1918: When escorting as an aux. cruiser a convoy for Norway torpedoed by the German UB 72 and sank on March 28 about 50 miles east of Aberdeen. Four British men lost their lives. Source: The Ships of Our First Century : The Effoa Fleet 1883-1983. Ed. by Matti Pietikäinen & Bengt Sjöström. Keuruu 1983, 231 p. ISBN 951-99438-5-4.” http://www.genealogia.fi/emi/emi321ne.htm

“Apart from Finns, the volumes record thousands of Russians, a number of Estonians, Latvians and Livonians. Many of the Russians have Jewish names, but even German names are common. To some extent there are separate books, but even books mainly recording Finnish emigrants contain such names. It is unclear wheher all Russian emigrants travelled by way of Hanko, since F.Å.A. boats carried Russian emigrants from Libau to Hull without calling at a Finnish port. Three or four times the F.Å.A. carried several hundred Russsian marines to Philadelphia, U.S. There was at least one voyage by an F.Å.A. boat directly to Philadelphia without a call at England.” http://www.genealogia.fi/emi/emi321ze.htm

“In 1906 the Wilson Line formed a separate company with the North Eastern Railway Company to integrate some of their rail and steamship services. This new company, the Wilson and North Eastern Railway and Shipping Company, made even greater profits by shipping and then transporting by rail the thousands of emigrants they brought to the UK each year. The new joint company limited the numbers who travelled via any other shipping or railway company and ensured a degree of continuity in the journey from steamship to quayside not seen at any other UK port of entry. Although it was the Allan, Cunard, Dominion or White Star Lines who sold tickets throughout rural and urban Scandinavia to would-be migrants for travel to America, it was Wilson ships which brought almost all the migrants to the UK – thus generating huge profits for their owners. The Wilson Line was at the time the largest privately owned shipping line in the world and its size accounts for the dominant role it held over the migration of thousands of Scandinavian emigrants between 1843 and 1914.” http://www.norwayheritage.com/articles/templates/voyages.asp?articleid=28&zoneid=6

“For much of this period Liverpool was, by far, the most important port of departure for emigrants from Europe because, as well as its established transatlantic links, Liverpool was well placed to receive the many emigrants from the countries of north western Europe, such as Scandinavians, Russians and Poles who crossed the North Sea to Hull by steamer and then travelled to Liverpool by train.” http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/maritime/archive/sheet/64

For additional information and a complete list of sources, see: https://www.wikitree.com/index.php?title=Fritzler-24&public=1

1 comment for “Carl Fritzler 1880-1963”